Why Zero-Shot Classifiers Struggle with Stereotype-Defying Cases

Proposal

For my project, I am interested in working on developing equitable image classification/feature detection tasks. Various work has been demonstrated that image classification accuracy can vary across socially meaningful groups. For example, Buolamwini & Gebru (2018) demonstrated that gender classification systems have widely varying accuracy rates across racial groups. While this represents a more arbitrary example of image classification accuracy bias, the canonical case is one in which image classifiers perpetuate a stereotype by inadvertently learning an association in training data. For example, a training dataset might contain more images of women cooking than men, and consequently an image classifier trained on such a dataset will perpetuate that observed association in test (Zhao et al. 2017).

Various approaches have been proposed for reducing/equalizing accuracy bias in image recognition tasks (Zhao et al. 2017; Hendricks et al., 2018). The primary logic behind these approaches is that the root cause of inequality in image classification accuracy is that image classifiers essentially learn associations between the group category and the image class from training data and then perpetuate that association inaccurately in test. The logic behind these approaches thus targets accuracy gaps that are specifically the result of unequal image class prevalence between groups in training.

I would like to rely on recently developed statistical methods to understand accuracy gaps in image recognition in a way that informs interventions. Yu and Elwert (2025) present a causal decomposition approach that allows a gap between groups to be decomposed into a set of sequential interventions. This approach is causally formulated, so directly informs real interventions in addition to providing an interpretable understanding of a gap between groups. The three sequential interventions provide four components. The first intervention is equalizing treatment assignment within groups (so that covariance between pre-treatment covariates and treatment assignment is zero within each group). The second intervention is equalizing treatment prevalence between groups (so that covariance between group membership and treatment assignment is zero within each group). The third intervention is eliminating treatment assignment entirely (what if no one received the treatment?).

I would like to extend this framework to understanding image classification accuracy gaps between groups. I would like to conceive of the image class as a treatment variable. For example, how would it look if the person in this image was cooking? My application of the casual decomposition would be slightly different from the original approach. Specifically, my decomposition would involve only three components rather than four, since a non-zero baseline gap in image classification in the absence of any image having the image class is impossible.

My primary hypothesis is that past research on image classification accuracy gaps has overlooked the role of differences in treatment selection in understanding and intervening on gaps in image classification accuracy. Previous research (as I understand it) focuses on gaps in prevalence. For example, images of people cooking are more likely to show women cooking than men, so image classifiers perpetuate that stereotype. My idea around differences in treatment selection proposes an additional mechanism. Keeping with the previous example, images of women cooking might show them in kitchens more, while images of men cooking might show them outside grilling more. Because one example (in the kitchen) is much more common in training data than the other (grilling outside), accuracy varies by cooking type, and consequently associated groups (gender).

I am still thinking through exactly how I will actually execute this project. My general thinking is something along the lines of obtaining an array of publicly available annotated images (like CelebA). Drawing on a small subsample of the available images, I would train an image classifier, test the classifier in some held-out data, assess gaps in accuracy between groups and decompose the gap. I would then leverage the results of the decomposition to inform an intervention to supplement the training corpus with specific new images (from the held-out data) to equalize accuracy.

Midterm Report

My project plan has not changed substantially over the last month, but has mostly become more refined as I have gotten more specific with the examples I am targeting. I have installed CLIP on my computer and have been playing around with it. I am now comfortable using it and having it do zero-shot classification. I am still setting up the specific examples I want to look at using it, but here is what I am thinking right now:

- COCO plus Princeton VisualAI. – A team of researchers annotated perceived race and gender for all people in the COCO 2014 Validation set. I just got approved today for restricted access to the race/gender annotations. The images and other annotations are already publicly available.

- More Inclusive Annotations for People – This publicly available dataset has annotations by gender and age group (child vs. adult).

- CelebA– This publicly available dataset has annotations by gender and age group (young vs. old).

- USGS EarthExplorer – This publicly available data covers satellite images for the entire United States, which I can geographically link to many other types of neighborhood data (racial composition, etc).

The main idea of the project is to adjudicate to what extent image classification models perpetuate stereotypes because of imbalances in training data versus imbalances in the extent to which a construct is associated with traditional versus non-traditional features (e.g., women cooking versus men grilling). I have a range of stereotypical constructs I plan to test through these datasets, and have verified for at least a few that the volume of images containing that action in a given dataset should be enough to have sufficient statistical power to do so. My current list of ideas is:

- Cooking vs. Grilling (gender)

- Household upkeep (Housecleaning vs. Yard work) (gender)

- Home Improvement (gender)

- Haircare (race)

- Childcare/leisure with kids (gender)

- Grooming (gender)

- Formal dress (gender)

- Exercise (gender; maybe race)

- Recreation (neighborhood racial composition)

Each of these represents what I consider to be a bundled construct that is made up of sub-activities/actions/objects, or features, which can be detected in images. I can identify images that show these constructs by matching from an expansive list of keywords and can identify the presence of specific features that fall within the construct using a combination of the annotations and matching the CLIP embeddings to word embeddings. Once I have done so, I plan to isolate four variations of a training set for each. The four training sets will correspond to a random training set, a training set with class frequency balance between groups, a training set with feature frequency balance between groups, and a training set with both class frequency balance and feature frequency balance between groups. I will then explore to what extent each potential training approach affects accuracy inequality between groups in a standardized held-out test set. As a robustness check, I plan to repeat the entire process with another embedding model besides CLIP.

The implications if my hypothesis is correct, and this is a source of bias, is potentially two-fold. One solution is to achieve balance between groups in terms of the sub-features. A secondary solution could potentially be to more equitably define constructs and potentially apply that improved/refined definition in annotation practices. For example, I am willing to believe an image of a woman in front of a stove is more likely to have the word “cooking” in the annotation than an image of a man in front of a grill might, because society has constructed a stereotype of what cooking is and should look like. Psychology suggests we tend to apply labels to the most distinctive features of an instance within its category, reinforcing narrow, stereotype-consistent definitions (Xu and Tenenbaum 2007).

Ultimately, I am still working on thinking of more potential constructs. Once I have a really big list, my plan is to see which constructs from the list I have enough statistical power for across the datasets and then include that subset in the final projects. I am assuming some of these just will not be well-represented enough in the datasets.

Replication code: https://github.com/vachuska/cs566

Final Paper

Introduction

As the scale and scope of machine learning models grow, the concern for how these systems exhibit bias and fairness rapidly grows as well. Research at the intersection of social science and artificial intelligence suggests that machine learning models risk learning the same stereotypes humans hold. When a machine learning model makes predictions based on group membership, it risks making classification errors that perpetuate stereotypes further, potentially even creating feedback loops (Brayne 2017).

Conventional wisdom suggests that the source of stereotypes is observed statistical associations between group membership and a trait or feature. Social psychology suggests that humans learn stereotypes as a mental shortcut for understanding the world (Koenig and Eagley, 2014). Machine learning models work similarly—given the goal of optimizing prediction accuracy, every piece of information that makes the prediction better is used—even if that means prediction errors are not equally distributed across groups. The logic behind approaches for eliminating stereotypes in human and ML models tends to be similar—purge the observed association and the biased prediction patterns go away too (Zhao et al. 2017; Hendricks et al., 2018).

Conventional wisdom behind defeating stereotypes aligns with conventional approaches for eliminating inequality more broadly. Sociological research has long focused on how mechanisms mediate the association between group membership and a particular outcome. For example, sociological research has long suggested that social origins are associated with social destinations because of educational attainment—break the association between social origins and educational attainment, and social origins will not be associated with social destinations (Hout 1988; Torche 2011). The logic for eliminating stereotypes in humans and ML models is similar: get rid of an observed association in training data, and errors will be equally distributed in test (Dasgupta and Asgari 2004; Kamiran and Calders 2012)

Recent statistical work in sociology complicates this mechanism-focused logic. Distinguishing between descriptive and causal mediation, Yu (2024, 2025) shows that even when groups have the same average level or prevalence of a mediating factor, inequalities in outcomes can persist because of differences in how individuals are selected into that mediator. More generally, this line of work suggests that equalizing exposure to a mediator is not always enough to equalize outcomes.

The increasingly diverse and expansive landscape of ML models and uses warrants increasingly diverse solutions for addressing equity. One of the most recent large-scale advances in vision models is the rise of dual-encoder vision–language models (Radford et al., 2021). These models enable zero-shot image classification, allowing the model to assign labels to images without any task-specific labeled training examples. Zero-shot image classification is enabled by dual-encoder vision–language models providing image embeddings that live in the same space as text embeddings. How close an image’s embedding sits compared to potential label text embeddings can be directly translated into classification probabilities. This approach has proven remarkably effective in practice, with CLIP-style models achieving strong zero-shot performance across a wide range of image classification benchmarks, often rivaling or surpassing supervised baselines (Radford et al., 2021).

Notably, zero-shot image classification is distinctive from other types of ML models. There is no single universal probability of a class occurring with such zero-shot image classification. Dual-encoder vision–language models function under the assumption that an image can be represented by a diverse array of vectors. Probabilities generated over a certain set of potential labels inherently assume exactly one shown label is correct. Probabilities are defined entirely locally, relative to whatever set of label prompts is supplied, and are entirely determined by proximity in the embedding space.

While zero-shot image classification can work remarkably well, its flexible nature makes it uniquely susceptible to certain issues. In a standard supervised classifier, a model can, in principle, learn that a label corresponds to a set of diverse visual patterns. As an example, in such a model, the decision boundary for “doctor” could, in theory, wrap around multiple, visually distinct clusters that all received the “doctor” label in training. By contrast, zero-shot classification from dual-encoder vision–language models treats each label as a single text embedding—a single prototype direction in the joint space that all positive cases are expected to align with. When the real-world cases associated with a label are internally diverse, this “single prototype” constraint means that some groups will sit farther from the label vector and thus face systematically higher error rates, even if the model has seen similar images in training.

Consequently, I argue that zero-shot image classifiers suffer from a unique source of stereotype-reproducing bias. Within a given class, if image diversity varies between groups, error rates are bound to be asymmetrical. This is a fundamental limitation of classification that relies on comparing individual instances to a single prototype. If individual instances are very diverse, no single prototype can sit close to them all. Furthermore, if individual instances are quite similar within one group, but quite different within another group, it can be natural to create a prototype that works well for one group, but not another—even when both groups are weighted equally. This notion challenges conventional wisdom for challenging stereotypes—equalizing group prevalence may not eliminate error patterns that align with the stereotype.

Both social psychology and sociology suggest that individuals whose traits and roles align with widely shared stereotypes are perceived as more “typical” group members and as forming a relatively homogeneous cluster, which makes them easier to categorize (Koenig and Eagly, 2014; Brewer et al.,1981). Processes of “subtyping” mean that people who violate stereotypes are often carved off into small, idiosyncratic exceptions or subgroups, so counter-stereotypical cases look more heterogeneous and difficult to categorize (Kunda and Oleson 1995; Deutsch and Fazio 2008; Gershman and Cikara 2023). For example, sociological work on racialized appearance shows that individuals whose physical traits more closely match racial stereotypes are treated as more prototypical and face stronger categorical responses (Eberhardt et al. 2006; Monk 2014).

Figure 1 points out a case of this. The figure contains two images of celebrities from the CelebA dataset. The figure on the left is coded as female, while the figure on the right is coded as male. Both figures are annotated as (and appear visually to be) wearing makeup, a physical appearance attribute commonly associated with females. The figure on the left uses makeup and has a general appearance that aligns with a traditional feminine appearance: long, styled hair, smooth skin, neutral eye makeup, and pink-toned lipstick that are common across many female-coded faces in the dataset. Distinctly, the figure on the right has a general appearance that does not clearly align with a traditional masculine or feminine appearance. While it is easy to pick out examples that share a wide array of physical appearance attributes with the figure of the female on the left, it is relatively difficult to find examples of males who share a wide array of physical appearance attributes with the figure of the male on the right.

In this paper, I propose and evaluate a novel explanation for the perpetuation of stereotypes, as applied to the specific case of zero-shot image classification models. In distinction from conventional wisdom, I demonstrate that zero-shot image classification models may misclassify in stereotyping patterns not because of training biases, but because stereotype-defying cases are more diverse—or at least are represented more diversely by dual-encoder vision–language models. I demonstrate this by drawing on annotated images of people from multiple datasets—considering groups in terms of gender and age, and stereotypes in terms of physical appearance attributes and associated objects. I show that stereotype-defying image cases have relatively weak within-group similarity, in contrast to stereotype-aligning image cases. I also explore how a training intervention to equalize group-weighting (the conventional recipe for solving stereotypes) fails to erase this effect.

Results

Figure 2 presents the results of the gender analysis on the CelebA data (the specific regression results are presented in Appendix Table S10). The x-axis depicts the gendered nature of a physical feature attribute. More positive values indicate an attribute is disproportionately common among males, while more negative values indicate an attribute is disproportionately common among females. The y-axis indicates differences in within-group cosine similarity between images of males and images of females. More positive values indicate that the set of male images where the person in the image has the physical feature attribute has higher within-group cosine similarity compared to the set of female images where the person in the image has the physical feature attribute.

I observe a clear, tight positive relationship in the data. The most stereotypically male attributes are characterized by sets of male images that sit in a relatively tight space compared to the respective set of female images. Similarly, the most stereotypically female attributes are characterized by sets of female images that sit in a relatively tight space compared to the respective set of male images. This relationship is tight—the amount of variation in the y-axis that the x-axis alone can explain (as indicated by adjusted R-squared) is over 50%. Figure 3 presents the same analysis for age, indicating a similar pattern (the specific regression results are presented in Appendix Table S11). This suggests that the observed pattern is not limited to gender as a grouping variable.

It is still fair to question whether or not the observed pattern is limited to certain sets of visual features. To address this, I additionally evaluate this hypothesis with objects in an image, conceiving of the typicality of an object based on how disproportionately common it is in images of males/females, or young/old individuals. Appendix Tables 12 and 13 indicate that the observed statistical association holds for this approach as well. Finally, I additionally explore this association in terms of text captions—the flip side of CLIP. I additionally tie in a social psychological measure of gender. Indeed, I find evidence that gender-defying images (as indicated by words found in the caption and the annotated gender of the person in the image) have relatively lower within-group cosine similarity. This result is presented in Appendix Table 14.

Next, I explore how the aforementioned differences in within-group cosine similarity mediate the association between feature typicality and inequality in potential zero-shot classification accuracy. Since zero-shot classification can be approached from essentially countless standpoints given the subjectivity of competitive classes, I analyze potential zero-shot classification accuracy from a best-case scenario. Centroid embeddings for a set of images generally correlate with the most optimal embeddings for zero-shot classification since the centroid approximates the idealized target vector that would yield the highest achievable similarity scores for that group under any zero-shot prompt. I can evaluate classification accuracy by looking at the 10th percentile of cosine similarity between all images and that centroid embedding. This effectively quantifies the lower bound of how well the least typical cases align with the group’s representation, and thus the plausibility of accurate zero-shot classification. I measure inequality in classification accuracy by taking the difference in the 10th percentile of cosine similarity between groups.

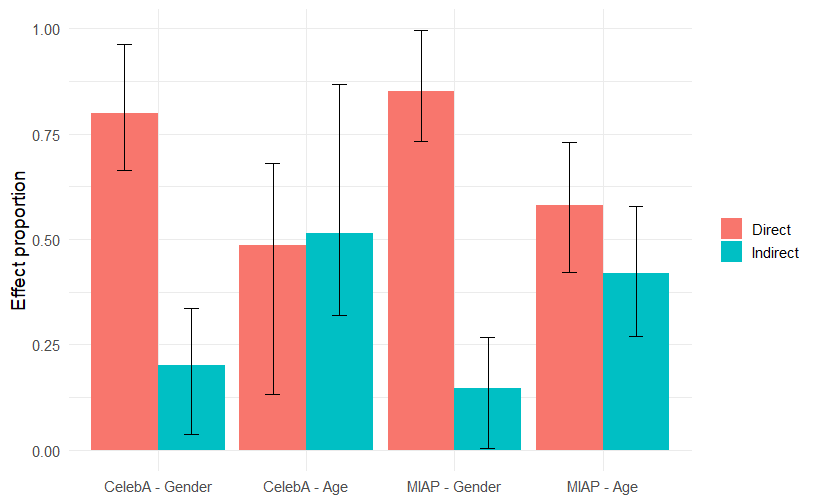

I first consider the centroid embedding to be the mean embedding across all image cases from all groups, weighing all observations equally. Using the Baron and Kenny (1986) method, I divide the proportion of the association between attribute typicality and inequality in classification accuracy into a direct effect and an indirect effect that operates through differences in within-group cosine similarity. Figure 4 presents these results across four combinations of dataset and grouping variable. Across all four cases, I find a significant and arguably relatively substantial indirect effect. Indeed, for age in the CelebA image dataset, the point estimate indicates that the majority of the association between typicality and classification accuracy operates through differences in within-group cosine similarity. The tables underlying these results are presented in Appendix Tables S15 through S18.

Next, I consider how a more equitable centroid embedding can shift the results. Classic efforts to debias ML models rely on purging biased associations in training data—the logic is that classification accuracy should equalize between groups if classes within groups receive equal weighting in training. To attempt this, I create a second centroid embedding that is equally weighted between groups—in this embedding both groups contribute equally to the centroid. Figure 5 presents the share of the direct and indirect effects that are erased by this training intervention. Across all cases, nearly all of the direct effect is erased. In distinction, little of the indirect effect is. In fact, in only one case is the share of the indirect effect erased, even statistically different from zero. The tables underlying these results are presented in Appendix Tables S19 through S22. Not only does this training intervention not block the indirect effect, but it also forces severe performance tradeoffs—substantially reducing classification accuracy for stereotype aligning cases as shown by Figures S1 and S2.

Discussion

In this paper, I have demonstrated an empirical regularity across CLIP embeddings: images that violate stereotypes constitute poorly defined groups, as measured by within-group cosine similarity. I have shown that this property holds true across both gender and age, across physical appearance traits, as well as the types of objects people appear with. Additionally, I have demonstrated an important consequence of this empirical regularity—it explains an appreciable share of why stereotype-defying cases are misclassified more often. Furthermore, its effect on classification accuracy is not susceptible to group-balanced training, the conventional approach for eliminating biases in ML models.

These findings have substantial implications for theories of stereotypes and inequality. My results echo longstanding work on prototypicality: members who strongly align with a stereotype are more similar to one another, while stereotype-defying members are more internally diverse. In geometric terms, this yields compact clusters for stereotype-consistent cases and diffuse, scattered regions for stereotype-defying cases. Echoing recent work by scholars, I argue that inequality cannot be fully understood by looking only at average differences in mediators between groups; the structure of how cases combine mediators matters (Yu 2024, 2025). My empirical application of this idea translates this insight into representation learning: even if average feature profiles are equalized, the distribution and dispersion of cases in embedding space can still sustain unequal error rates. These findings potentially have implications for understanding how stereotypes are perpetuated among humans. While I have no empirical evidence that human stereotypes behave similarly or operate through a similar mechanism, future research may empirically test such an idea.

This research also has several implications for zero-shot models and fairness in ML. While much ink has been spilled on debiasing and fairness solutions in ML, to the best of my knowledge, this is the first time this particular mechanism has been highlighted in research. Notably, this documented empirical regularity is not fixable by simply balancing training examples across groups, as is used elsewhere. Applications that rely on zero-shot models should be scrutinized for the phenomenon documented here. While the empirical regularity documented here appears relatively robust, not every classification task inherently suffers from it. There may be certain classification tasks where stereotype-defying cases are as tightly defined as the stereotype-aligning case is. Researchers and actors who apply zero-vision language models should, in any case, be cognizant of the possibility of the phenomenon.

Researchers should explore design strategies and potential interventions to solve this problem. A major advantage of CLIP and zero-shot classification is the global applicability of the architecture to a universal array of images and image classification tasks. However, the major pitfall of that issue is that when issues are identified, they can often only be solved by universally transforming the model’s geometry. Interventions that target fixes for specific classification problems are not guaranteed to work globally, and fine-tuning away the problem will not affect zero-shot classification. Instead, in order to solve the issue, the entire geometry of CLIP embeddings needs to be revised so that classes of images are similarly well-defined regardless of whether they are stereotype-defying or stereotype-aligning. While proposing a specific solution is well beyond the scope of this paper, approaches to geometric transformations that de-emphasize stereotypical constructs and emphasize features that bridge groups are theoretically likely to be the most effective.

While I have explored the hypothesized empirical regularity across multiple datasets, axes, and stereotype forms, this research is not without limitations and scope conditions. I have documented the observed empirical regularity in terms of stereotypes defined by physical appearance attributes and objects individuals appear with, but there are potentially other ways that stereotypes can be defined, for which the empirical regularity may not hold. Future research can continue to test the main hypothesis across more approaches for defining stereotypes. Similarly, the research here focused on only two axes of inequality—gender and age. Much stereotype research focuses on race and class. It is possible that these hypotheses do not hold for these groups. Finally, the empirical approach here focused on abstract classification logic, without considering real-world classification problems where images are probabilistically assigned to competing text class labels. While the empirical analysis provides general evidence that differences in within-group cosine similarity shape inequality in classification accuracy, without looking at real-world cases, it is difficult to fully quantify the magnitude of this effect. It is possible that in practice, this is a relatively minute problem. Nonetheless, the point of the analysis was to highlight that, in principle, it could be a very substantial problem. Since zero-shot image classification is renowned for its flexible applications, it is especially important to generalize potentially major issues.

Ultimately, future work can extend these analyses by examining whether similar geometry-driven disparities arise in other foundation models and modalities, conducting behavioral studies that compare representational geometry to human stereotype use, and empirically evaluating interventions, such as multi-prototype prompts or representation regularization, that explicitly target within-group dispersion.

Taken together, these results suggest that unequal performance in zero-shot image classification can persist even when models are trained on seemingly equitable, balanced data, because stereotype-aligned and stereotype-defying cases occupy systematically different regions of representation space. This links sociological and psychological accounts of prototypicality and subtyping to the internal geometry of foundation models, highlighting a structural source of inequality that cannot be addressed by reweighting data alone. Designing fairer systems will require not only parity in who appears in the training set, but also attention to how models represent the full diversity of ways that social categories can look in the world.